History of UT Entomology Part 3: Oz's Mosquitoes and Beetles

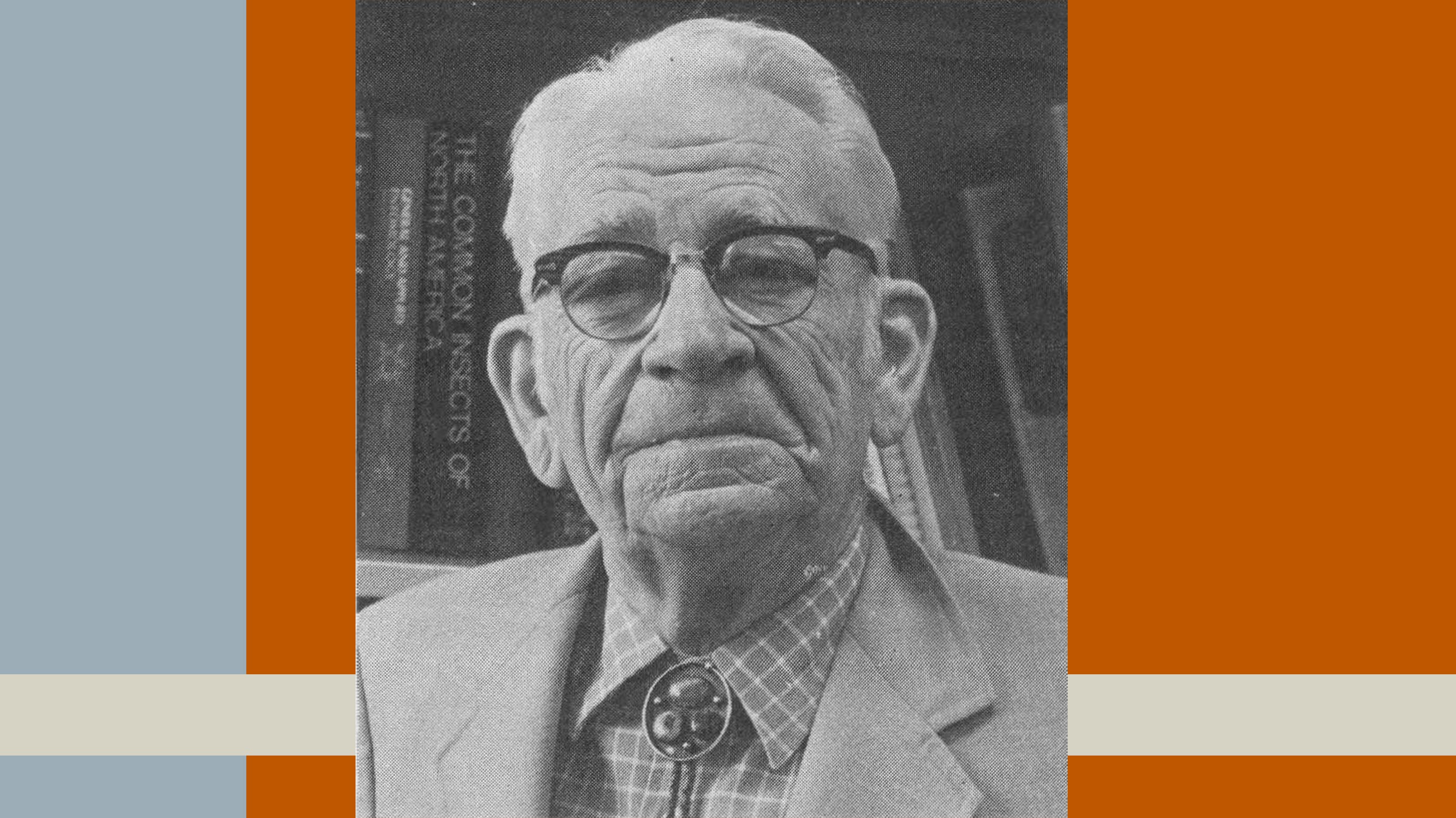

As explored in Part 2 of our series, the Drosophila group at UT was still active in the late 1930s, researching genetics through the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, as well as Drosophila diversity. But there were other entomologists at UT using different insects for their work around the same time. One was Dr. Osmund P. Breland (1910-1984), known to many simply as “Oz.” He not only collected and identified mosquitoes, but did systematics work. He also made an important discovery with whirligig beetles.

Breland was born on September 17, 1910 in Decatur, Mississippi. Even as a child, his interest in insects was apparent. As a boy, he was fascinated with ants and spent hours observing their behavior.

In 1931, he graduated with a B.S. from Mississippi State University. He attended graduate school at Indiana University where he received his Ph.D. in 1936. His research was on the biology and taxonomy of callimomid wasps under the guidance of Alfred C. Kinsey, an American biologist, professor of entomology and zoology, and a sexologist, the latter being what Kinsey is best known for. As Breland was always interested in insect parasites, he and colleagues at the University of Indiana collected gall wasps extensively in Mexico in the mid 1930s.

After a short stint as an instructor at North Dakota State University, he accepted a position in the Zoology Department at UT Austin in 1938. He was promoted to Assistant Professor in 1942, but then entered the U.S. Army in 1943 as 1st lieutenant during World War II. During this time, Breland worked in the medical entomology branch in Panama. It was here he would develop a career-long interest in the biology of mosquitoes, including those that are disease vectors.

Breland (right) with entomologist, John Rawlins, at UT in the early 1980s.

The World Health Organization defines disease vectors as “living organisms that can transmit infectious pathogens between humans, or from animals to humans. Many of these vectors are bloodsucking insects, which ingest disease-producing microorganisms during a blood meal from an infected host (human or animal) and later transmit it into a new host, after the pathogen has replicated.” Many commonly-known mosquito diseases include malaria (transmitted by Anopheline mosquitoes), dengue, Zika, and Yellow Fever (all transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes).

After the war when Breland returned to UT Austin, he would teach entomology and parasitology. He and his graduate students studied the larval biology and breeding areas of Texas mosquitoes. Most of Breland’s technical articles deal with these organisms, and to most current researchers, his work on the taxonomy and bionomics of a number of Texas mosquitoes is what he is best known for. In his 1959 paper “Preliminary observations on the use of the squash technique for the study of the chromosomes of mosquitoes,” he described a simple method of preparing larval brain chromosomes for study. This would pioneer much of the later work in mosquito cytology and cytogenetics.

Perhaps a little history of mosquito research in Texas is in order. Mosquito systematics began in the early 1900s with the USDA Bureau of Entomology. Texas was an area where collectors from Washington DC would come to collect every type of mosquito. In response to the federally-funded malaria eradication program, the Texas Department of Health began to collect and identify mosquitoes. Public Health Service entomologists published information about their collections as well as their travels, and soon more Texas researchers would become involved with collecting and identifying species. However, these researchers did not usually do systematics, the process of evaluating specimens to determine if they should be the same or different species.

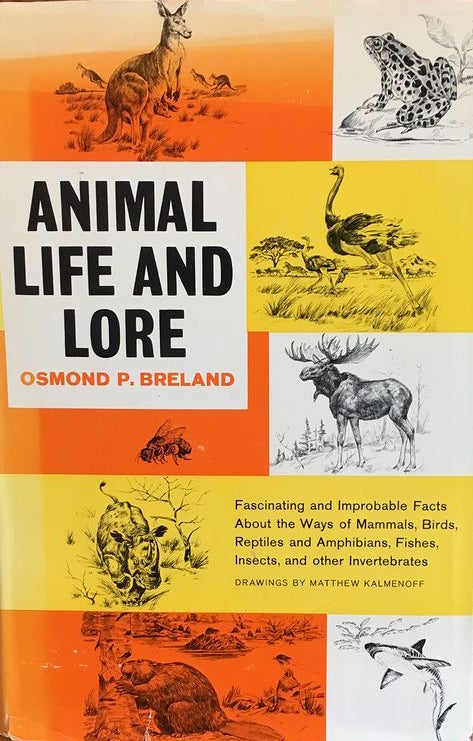

Breland also wrote both academic texts and numerous taxonomic works, one example being Keys to the Larvae of Texas Mosquitoes. He also wrote works for a more general audience, titles like Animal Facts and Fallacies (1948) and Animal Friends and Foes (1957), both combined in 1963 under the title, Animal Life and Lore. These books started from questions he would receive from both students as well as the general public, questions he could not answer but would research, accumulating what he called “fairly useless information” in the form of clippings and magazine references. His intention was to create a book people could turn to for common entomological and zoological questions like “How do ants swarm?” and “What insects live the longest?” These books were quite popular for the time and were translated into several languages.

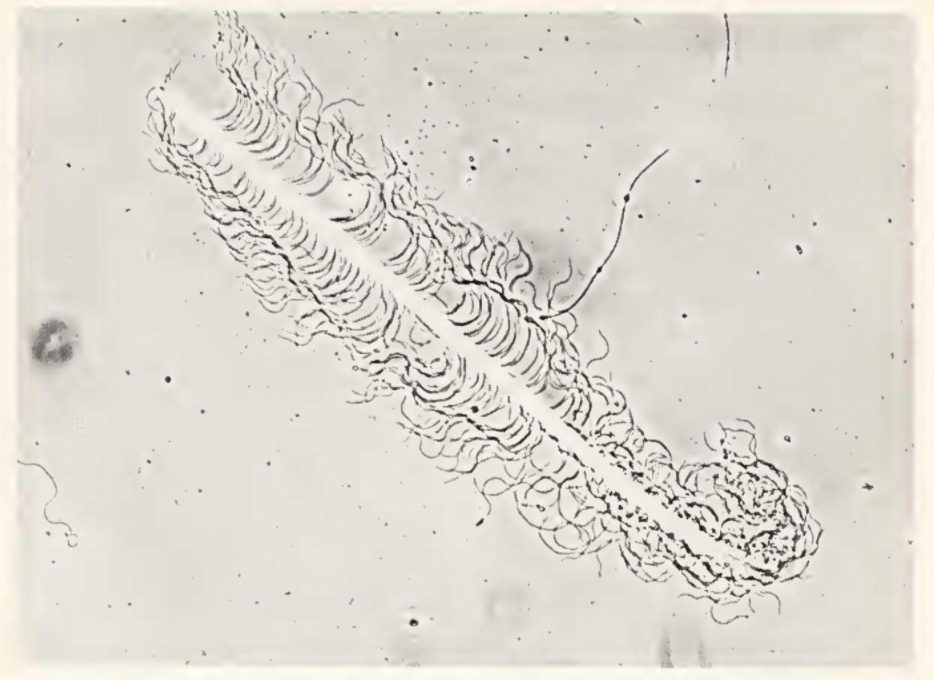

Outside of his work on mosquitoes, Breland spent the last phase of his scientific career in the cytological study of insect sperm production. He and a graduate student, Everett Simmons, discovered a unique feature of the sperm of whirligig beetles (Coleoptera Gyrinidae), a family of water beetles. Male whirligig beetles embed their sperm in a spermatostyle, a non-cellular rod. Once the spermatostyle is released, the sperm then cooperatively propel themselves to the spermathecae, an organ of the female reproductive tract in in invertebrates and certain vertebrates. As Breland was not an evolutionary biologist, it didn’t strike him at the time the significance in social biology of discovering sperm cooperating to get someplace. Luckily, recent interest from evolutionary biologists in sperm competition has brought attention to Breland’s and Simmons’ discovery.

Whirligig beetle spermatostyle

People that knew Breland described him as “fulgent” (glisteningly bright) and a “stickler to facts.” Breland had a low tolerance when it came to flamboyant writing and academic bureaucracy, but a talent in teaching his students how to properly navigate both. He also enjoyed playing poker, so much so that he had a book in his personal library all about how one could make a living at the game.

In 1972, American entomologist, Thomas Zavortink, named a mosquito after Breland: Aedes brelandi.

Breland was a smoker, and sadly would die of emphysema in 1984 at the age of 74. He is buried in the Austin Memorial Park Cemetery. Many of the mosquitoes and wasps that Breland collected are now housed in the UT Entomology Collection.

In our next article, we will look at the screwworm fly, (Cochliomyia hominivorax), the decades of devastation it brought, and how UT researchers had a hand in bringing it under control.

Special thanks to Dr. William Sames for his contributions and edits to this article.

Check out all of our UT Entomology History blogs here…

What the heck is...?Cytology: the study of cells as fundamental units of living things, also known as cell biology. Cytogenetics: a branch of genetics, also part of cytology, concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behavior. Systematics: the study of the kinds and diversity of organisms and the relationships among them, evaluation of specimens to determine if they should be different or the same species. Most Texas researchers have been involved with collections and identifications, but not systematics. However, all three are important. Taxonomy: the theory and practice of identifying, describing, naming and classifying organisms |

SOURCES

Correspondence with Dr. William Sames

Correspondence with Dr. Larry Gilbert

Breland, Osmund P. and Simmons, Everett. “Preliminary Studies of the Spermatozoa and the Male Reproductive System of Some Whirligig Beetles (Coleoptera Gyrinidae)” Entomological News, May 1970. p. 101

Long, James. D. “Obituary: Osmund P. Breland, 1910-1984.” Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. 1985. Vol. 1, No. 2, Pg. 266

World Health Organization. “Vector-borne diseases,” March 2, 2020 (accessed online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases)

Zavortink, Thomas J. Mosquito Studies (Diptera, Culicidae) XXVIII, 1972. The New World species formerly placed in Aedes (Finlaya).