A Look at the Life of Geneticist Hermann J Muller - Part II

Left: Muller in his UT office, BIO 325. Right: Muller in 1922.

TROUBLE IN TEXAS

As mentioned in Part One of this article, Hermann Muller was becoming a superstar in the science world of the 1920s. His talks and research on X-rays causing mutations in the fruit fly Drosophila were receiving world-wide attention. The size of his lab at UT Austin was increasing. But his long work hours and animosity towards his colleagues at UT were beginning to cause trouble. In addition, the development of politics and world affairs in the 1930s caused Muller to become attracted to communist-leaning ideals. This spelled trouble in a USA very much opposed to these ideas.

Muller had met Jessie Jacobs, an instructor in pure mathematics, while at UT. They would marry, and when Jacobs became pregnant with their first child, she would lose her position because at the time, her colleagues felt that a mother could not give full attention to classroom duties and remain a good parent. Jessie’s loss of her connections to her academic career would bring strain into the marriage, in addition to Muller's long night hours at his lab.

Muller’s relations with Painter and Patterson also began to deteriorate in 1929, with Painter skeptical of radiation causing reverse mutations, and Muller feeling Painter and Patterson were using his ideas and taking too much of his time. In addition, his formal mentor, Morgan, was still being acknowledged as the power center of genetics, despite all of the work Muller had done in Texas.

With the start of the Great Depression in the US, and the huge rise in unemployment, Muller felt burdened by the economic reality of many Americans suffering through this hardship. While most of his beliefs seem quite reasonable today (equality in wages for women, civil rights of African Americans), Muller's concern for the state of poor Americans was considered communist at the time. Even with the knowledge of the trouble this could possibly bring him, Muller served as faculty advisor of the National Student League, a student-led organization at UT that was also a communist front, advocating for things such as lower tuition rates, political and social equalities for minorities and blacks, and unemployment insurance.

On January 10, 1932, Muller wrote a note to fellow geneticist Edgar Altenburg. In the letter, Muller commented on his work as a scientist, writing that he was "too psychologically old to continue the struggle." He also requested that Altenburg give $1000 of Muller's money in support of the Communist Party. Muller then headed out to the woods outside of Austin and swallowed a roll of sleeping pills. He failed to show up to class the next day, and his wife frantically called his lab as he had not come home the night before. Several of Muller’s students and staff formed a search party, eventually locating him dazed under a tree but still alive.

While gossip about his suicide attempt spread, Muller quickly recovered, and in a complete turn of events, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship to study at the Institute of Brain Research in Berlin. This was very much a relief, for Muller could sense his days in Texas were numbered.

In his paper "The Dominance of Economics over Eugenics," Muller had quite publicly condemned the eugenics movement at the Sixth International Congress of Eugenics, arguing against current eugenics assumption that socially undesirable traits like vagrancy were innate. Muller instead argued that socially undesirable traits were a result of social situations. At the time, this was a very Marxist position, and considered outrageous.

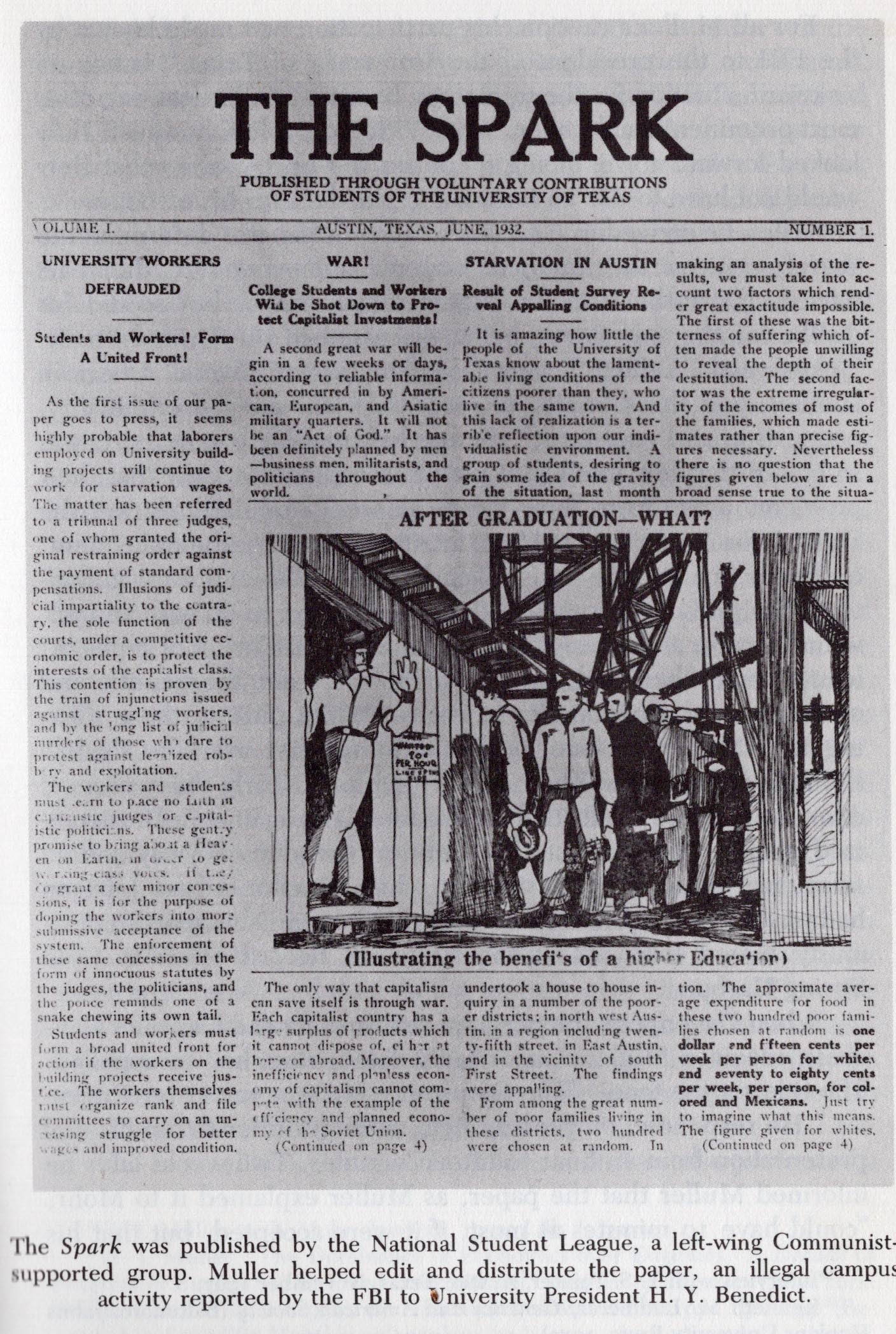

In addition, Muller had by now opted to sponsor the newspaper the UT National Student League wanted to distribute. It was called "The Spark" and represented the left-wing views of the League, but it would not be permitted at the university. Despite the possible repercussions he could face at the time, Muller opted to help get it into print and distributed. He was unaware that the FBI had had infiltrated the National Student League, and also had Muller under surveillance. The FBI made this involvement known to then President of UT Austin, who was only relieved to know Muller would be leaving soon for Berlin.

With all of this stress, by the end of 1932, Muller and his wife, Jessie, had agreed to a separation.

GONE FROM TEXAS

With these mounting pressures, Muller went overseas to Germany. However little he took Hitler seriously at first, Muller soon faced the reality of the danger of Nazi takeover when the Nazis vandalized the institute where Muller was working. Muller opted to accept an invitation to establish a genetics laboratory in the Soviet Union where interest in genetics was growing.

Muller's five years in the Soviet Union changed a lot for him. Free of teaching duties, he became senior geneticist at the Soviet Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Genetics in Leningrad and Moscow. He had a lot of support and built a lab to initiate a focus on gene function explored through the "position effect," the position effect implying that the functioning of a gene is to a certain extent at least dependent upon what other genes are in proximity. Muller felt an admiration of Soviet life and socialism, and even Jessie and their son David came to live in an attempt to reconcile the marriage.

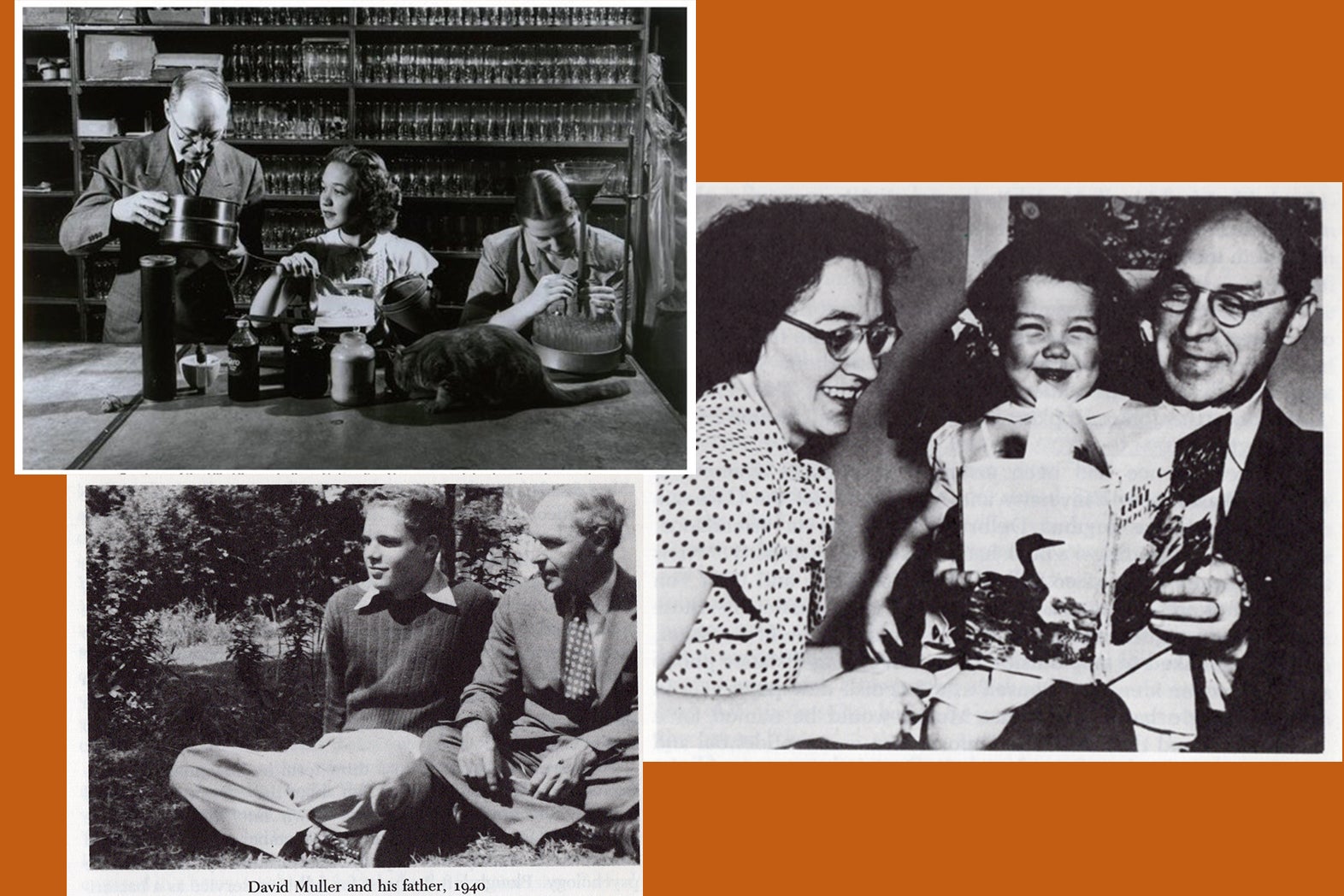

Despite this upturn in events, trouble would find Muller again. The move to the Soviet Union did not help Muller's marriage, and it was dissolved in 1935 after Jessie and their son returned to the States.

Muller found more trouble in his attempts to launch a eugenics program in the Soviet Union. Muller wrote a letter to Stalin advocating his ideas of a positive eugenics program, but there was a counter movement occurring. Trofim D. Lysenko offered a different view of heredity, based on his experiments with plant breeding, and upheld Lamarckian ideas in which the environment modifies genetic material in a direct or predictable way. Lysenko viewed western genetics, and thus Muller's views, as capitalist, racist, and bourgeois.

A very heated debate would occur, with Muller on one side and the Lysenkoists on the other. Simultaneously, many of Muller's colleagues would suffer from Stalin's purges, accused of being Trotskyites, leading to their arrests and execution. In a mass meeting of 3000 people, Muller debated Lysenko, essentially calling him a fraud, and causing an uproar amongst those supporting the Party agenda, and thus Lysenko. Advised to leave for his own safety, Muller enlisted as a volunteer in the Spanish Civil War in 1937 for the International Brigade, to combat Franco's fascist rule. Here he would do physiological research on blood transfusion.

Staying in Spain through the siege of Madrid, Muller needed to find a new place to go but had few options. His involvement in the communist-leaning UT student paper would force him to stand trial if he returned to UT. He could not return to the Soviet Union or face the possibility of execution. His wish was to work in Paris with Joliot Curie or in Stockholm with Gunnar Lundburg but there were no job openings.

Muller at a masquerade party in Edinburgh, 1939. He is the pirate lying on his side at the very bottom. (Photo from the Lilly Library, Indiana University)

Through the influence of Julian Huxley, in 1937 Muller joined the Institute of Animal Genetics at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, where he developed a graduate program. Muller began to research the relationship of radiation dose to mutation frequency. He would advocate radiation safety and human use at a time when it was largely misunderstood. Muller remarried in Scotland and earned a doctorate of science in genetics in 1940.

However, Europe's tense midcentury political landscape would drive him once again from his home. World War II broke out, and Great Britain essentially shut down research in an effort to focus on the war at hand. In 1941, Muller moved to Amherst College in the US. During the war's slimming effect on research, Muller consulted on radiation projects for the Manhattan Project, in addition to teaching undergrads, something he did not care for much.

At the end of the war, with the knowledge that he would not be added to the Amherst faculty, he appealed desperately to friends to pull strings. Luckily, his reputation opened the door to become faculty at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.

Top left: Muller with staff and a cat in the Fly Room at Indiana University (Photo from the Lilly Library, Indiana University) Bottom left: Muller and his son David in 1940. Right: Muller with wife Thea and daughter, Helen, around 1946. (Photo from the Lilly Library, Indiana University)

Muller would spend the rest of his teaching years here, and these were some of his happiest. He felt appreciated by his colleagues and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1946, which had a transforming effect on his career. He was able to work on new problems in human genetics. He also had a daughter with his second wife.

During his tenure at Indiana University, Muller spoke out against radiation abuses during a time when this stance was read as a political attack against national security, and thus defending Communism. In an effort to protect his students and colleagues, he also burned much of his correspondence with communists during this era of McCarthyism, and had to testify before the House of Un-American Activities.

Muller also revived his ideals of eugenics, and felt that it could be used essentially like family planning to produce healthier, more intelligent and caring future generations. But in the shadow of the Holocaust and early American eugenics movements, his beliefs on how to apply this were very often misunderstood and as a result, condemned.

Muller receives the Nobel Prize from King Gustav V of Sweden, 1946 (Nobel Foundation). (Click to expand view)

In 1964, Muller would suffer a severe heart attack that affected his health greatly. In the following years, his health would worsen, eventually leading him to the hospital for kidney failure on his 76th birthday. Muller’s condition did not improve, and he decided that he no longer wished to live, something he accomplished by refusing to eat. He died in Bloomington on April 5, 1967.

Herman Muller was a scientist passionate about his work, and equally passionate about speaking out against the abuses of science. He helped usher the careers of many of his students on whom he made a deep impression. Muller also found himself directly involved in some of the most tumultuous times in history, from the era of the Great Depression and tolerance of racism in the US, to the anti-Semitism and book burnings of Nazi Germany, to Stalin's purges. Despite his troubled and intense life, Muller left a lasting impression on the field of genetics, much of this influential work happening while here on the UT campus.

Muller on his last hike with his second wife, Thea. 1964. (Photo from the Lilly Library, Indiana University) (Click to expand view)

INTERESTING TRIVIA

- UT’s first female Ph.D. in Zoology (1931), Bessie League, assisted in Muller's lab. Her office number in BIO was room 313.

- Muller and science fiction writer Ursula Le Guin are second cousins.

- Carl Sagan worked in Muller’s lab at Indiana University during the summer of 1954.

- At a time when air conditioning was decades away, the "constant temperature room" in UT’s "Fly Room" was kept at 69 degrees year round for raising Drosophila during the hot Austin summers. You can read about my long search for Muller's Fly Room on the UT campus.

- Muller’s granddaughter, Chandra Muller, is a professor in the Department of Sociology at UT.

- Muller’s son, David E. Muller (1924-2008), speaks frankly about his father in these video recordings on the Oral History Collection project from The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (http://library.cshl.edu/oralhistory/interview/scientific-experience/becoming-scientist/discussions-his-father/)