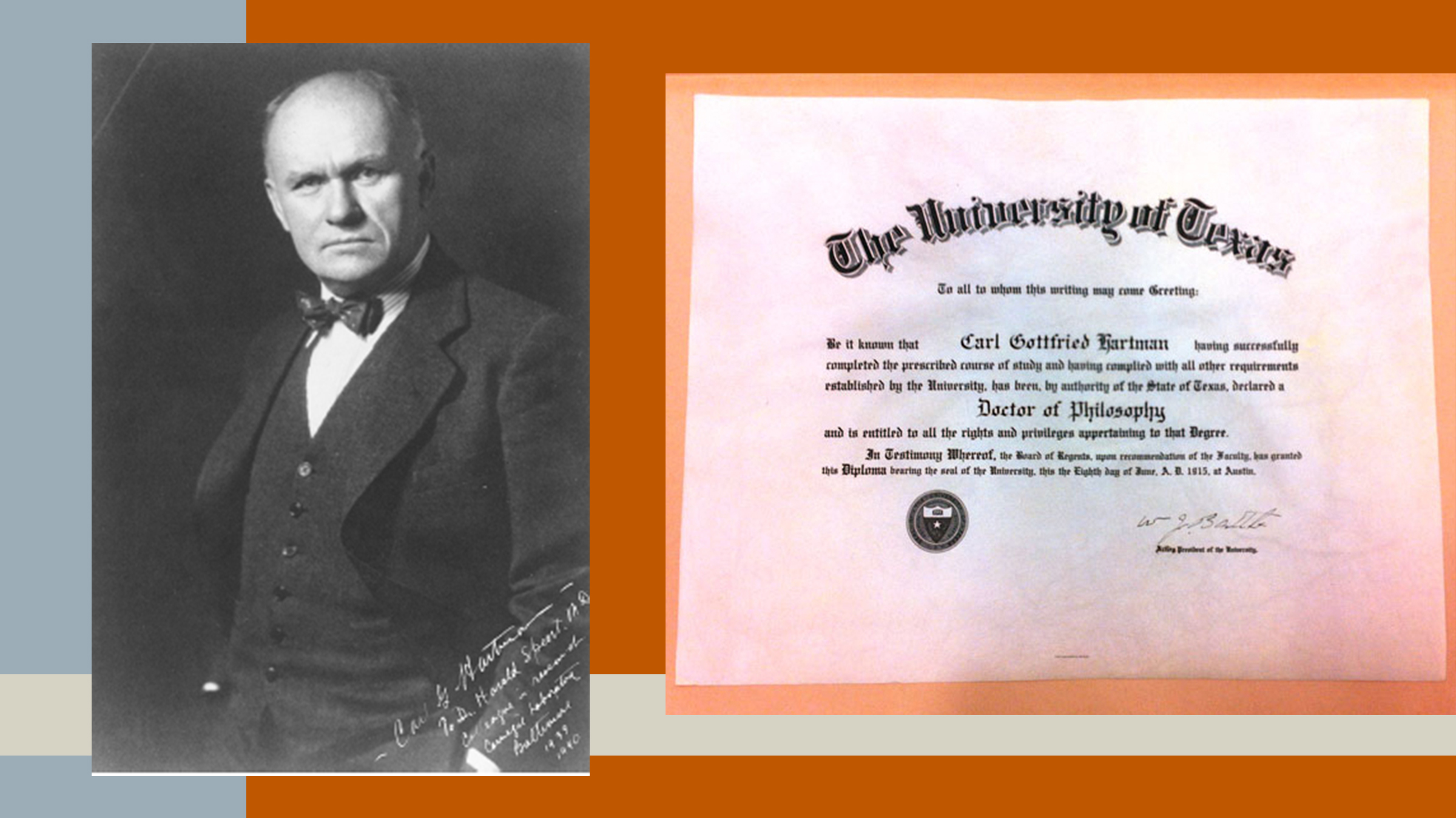

Biology at The University of Texas at Austin traces back to the very beginnings of the University. The first Ph.D. ever awarded at Texas was given to Carl G. Hartman, a student in the School of Zoology, on June 8, 1915. In the 1916 edition of the Cactus Yearbook, we can read of his graduation that "as he mounted the steps to the platform, the entire body of graduates rose and gave him an ovation." In the century-plus since then, there has been tremendous growth and change in biology at The University of Texas.

Nicole Elmer, Communications Coordinator for the Biodiversity Center, laid out this history in detail in a series of researched articles for the department.

History of Biology at UT

History Overview of the Department of Integrative Biology

The University of Texas at Austin has a storied and long history of leadership in biology.

The Old Main Building, original home of the School of Biology, and later of the Schools of Botany and of Zoology, was torn down in 1934.

Left: Dr. Carl G. Hartman, from an Experientia in Memoriam article by R. F. Vollman. Right: Hartman's 1915 PhD, housed in the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

A photo of Hartman, dedicated to Harold Speert. From "Memorable Medical Mentors".

Morrow in her lab. Left: photo from 1944. Right: photo from 1943.

Left: Hilda Rosene Florence (from John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation) Right: Rosene, standing center at 1951 a UT dinner honoring J.T. Patterson, seated on the bottom right.

Left: Muller with his jeweler's loupe, a fly viewing practice he picked up while working in the Morgan lab. (Photo in UT Zoology Archive, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin) Right: article image from piece written by C.P. Oliver

Left: Muller in his UT office, BIO 325. Right: Muller in 1922.

Left: Delco at home during an interview with the author.

The photo of the Fly Room that launched the search. (Dolph Briscoe Center for American History)

Elmer Julius Lund (UTMSI)

Left: Power House and dam, 1892. Right: The aftermath of the dam break.

Right: From "Ants, Their Structure, Development, and Behavior" (1910)

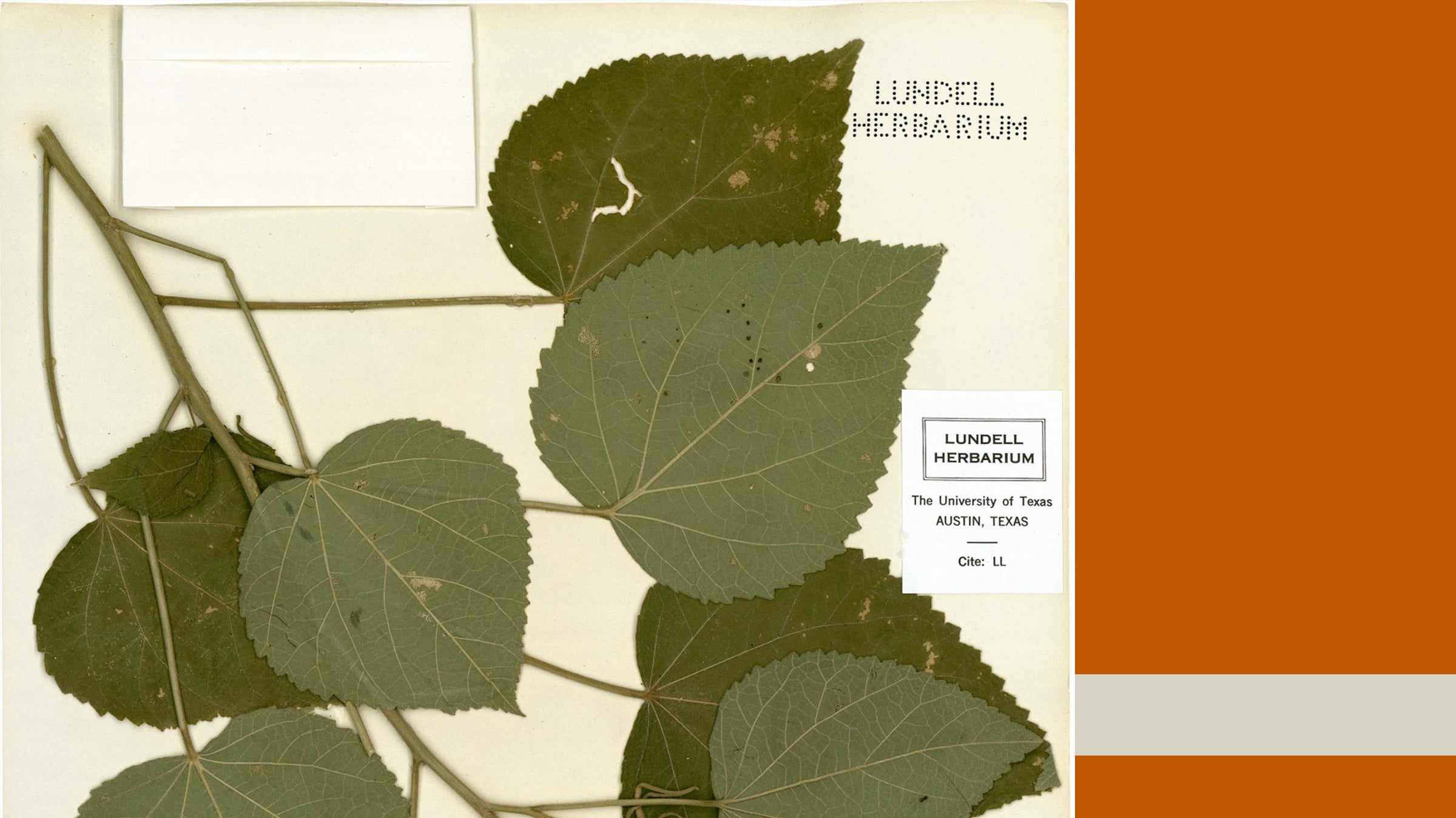

Section of Lundell Herbarium 1964 specimen of Hibiscus lasiocarpus Cav.

Simpson in 2008 in southern Argentina (Nuequen) collecting Adesmia.